The Forgotten Legacy of Turtle Mountain — and Why It Matters to Métis Rights Today

I’ve been on a personal crusade lately — one that begins at Turtle Mountain, stretches across the Canadian Prairies, and uncovers a long pattern of Métis exclusion from land rights, despite their direct involvement in treaty-making.

Most people don’t know that Turtle Mountain, now a recognized reservation in North Dakota, was founded under a treaty in which Métis leaders — Jean and Isidore Dumont — were installed as chiefs through Anishinaabe insistence. It’s also the only reserve in the U.S. that officially recognizes Métis leaders as part of its origin.

But what’s even more significant — and legally explosive — is this:

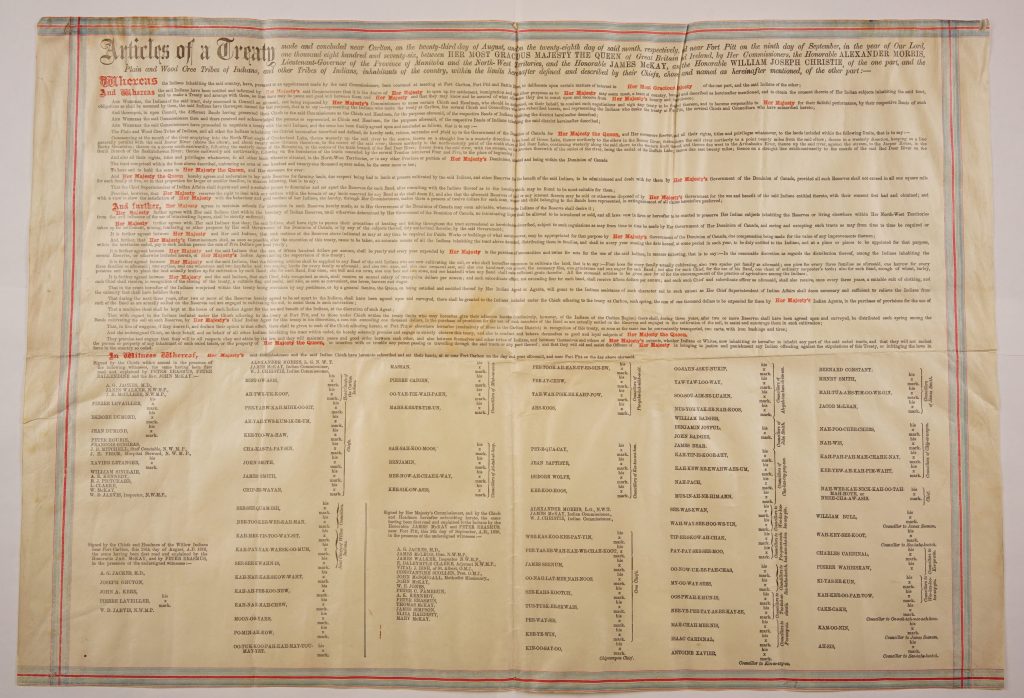

Jean and Isidore Dumont were signatories to Treaty 6.

Yes — their names are written directly on the treaty document. This fact alone shatters many of the artificial legal boundaries Canada has maintained for more than a century.

Treaty 6 Was Not Exclusively “First Nations Only”

For years, Canada has drawn a hard legal line between:

- “Treaty Indians,” supposedly represented only by First Nations signatories, and

- “Métis,” who were supposedly excluded from all numbered treaties and left with no treaty-based rights.

This line is false.

Proof? The Dumont brothers signed Treaty 6.

They were not simply witnesses or advisors. They were recognized leaders, both by Indigenous nations (like Beardy and Mistawasis) and through their own Métis community of Turtle Mountain. Their presence was not symbolic — it was political, legal, and territorial.

If Métis leaders signed the treaty, then Métis rights exist within that treaty.

If Turtle Mountain’s chiefs were signatories, then Turtle Mountain is Treaty 6 land — regardless of whether Canada chose to map it or not.

A Pattern of Recognition — and Then Erasure

The Dumonts were not the only Métis to participate in treaty affairs. The historical record shows:

- They were recognized as chiefs at Turtle Mountain.

- They assisted in treaty negotiations at Duck Lake, where Mistawasis asked how Métis living among the Cree would be treated.

- Commissioner Alexander Morris gave a legally evasive answer: “Some Half-breeds want to take lands at Red River and join the Indians here, but they cannot take with both hands… The small class of Half-Breeds who live as Indians and with the Indians, can be regarded as Indians by the Commissioners, who judge each case of its own merits.” (Christensen, p. 269)

Despite this careful language, Morris signed a treaty that included Métis leaders on the list of signatories — the Dumonts among them. That contradicts the policy of exclusion that followed for decades.

What the Indian Claims Commission Confirmed

The 1997 Indian Claims Commission (ICC) hearing on the Canupawakpa Dakota Nation revealed a consistent pattern: when Indigenous peoples did not fit Canada’s strict legal identity boxes, they were simply denied treaty participation, even after settlement.

“There is evidence on the record already that the Dakota leadership that came into Canada… were the remnants of the people who had experienced genocide… and they came into Canada looking for refuge and freedom.” — Norman Bone, ICC

But when it came time to formalize land rights:

“Canada, in fact, was very welcoming at first. And then when it came time to sign treaties, there was the issue of: well, these are not our Indians… they’re refugees, and they’re Americans.”

This exclusion applied equally to Métis-Dakota communities like those at Turtle Mountain. Even with clear Indigenous kinship and political ties, Canada drew a line to avoid land obligations.

Legal and Constitutional Implications

Because Treaty 6 contains the signatures of Métis leaders, including those representing Turtle Mountain, the following legal consequences apply:

- Turtle Mountain’s Canadian half is Treaty 6 territory

- The community’s leadership signed the treaty.

- Their authority was recognized by Treaty 6 signatories.

- Their people lived on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border before and after the treaty.

- Canada has a constitutional duty to recognize Métis treaty rights

- Under Daniels v. Canada (2016), Métis fall under s.91(24) of the Constitution — same as “Indians.”

- Under R v. Badger and Mikisew Cree, treaty interpretation must honor oral promises and Indigenous understandings.

- Canada’s historical refusal to provide Turtle Mountain Métis with land, services, or recognition is a breach of Treaty 6

- The Dumonts’ signatures are legal proof of Métis inclusion.

- The exclusion that followed is not just a moral failure — it is a violation of treaty law.

Letters Sent — And What Needs to Happen Next

I’ve already sent letters to federal and provincial governments demanding:

- Recognition of Turtle Mountain’s Treaty 6 status

- A formal investigation into Canada’s post-treaty exclusion of Métis signatories

- Restitution for the deliberate erasure of the Canadian half of Turtle Mountain, where Métis leadership once stood

So far, the responses have ranged from silence to bureaucratic misdirection. But this new evidence — the Dumont signatures on Treaty 6 — changes everything.

Final Thought

If the Métis signed Treaty 6, then Métis people are part of that treaty.

If Turtle Mountain’s leaders signed, then Turtle Mountain — including the part in Manitoba — is Treaty 6 land.

This isn’t just history. It’s a standing constitutional issue. And it’s time Canada was held to account.